Embroidery in apartheid

From Palestine to Johannesburg, a look at textiles for healing, justice and rebellion.

“The dress is resistance. The dress is a rifle. The dress is the bullet that will scatter into the faces of our enemies. Some fight with weapons but we fight with our dress.”

Those are the words of Samira, a Palestinian woman emphatically discussing the role of her traditional dress (source).

Not to sound like a Catholic, but there’s great beauty to be found in suffering. For the past 4 years, I’ve been singularly obsessed with historical fashion which, as a Black person, can sometimes seem like an exercise in self-harm. For every magnificent hoop skirt, corset or tapestry I come across, there is often a dark underbelly of forced labour, colonialism and erasure.

I like Marie Antoinette’s chemise a la reine but it also fueled the chattel slavery-backed cotton industry. I admire the harmonious patterns in shweshwe but it was brought over by the occupation of Indonesia. I want to recreate the clothing of my ancestors but an apartheid system didn’t value it enough to archive.

And yet, I persist.

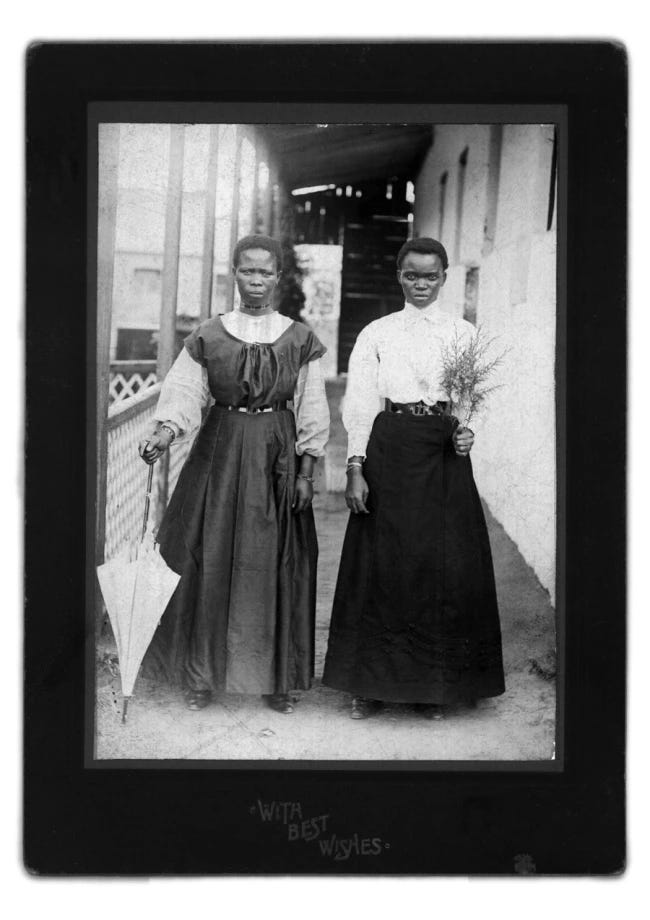

Historical representation of people who look like me is rare so it’s always a joy I must share when I do come across something. And yet, when I unearth Black Victorians or Sophiatown teenagers, some people cannot share my enthusiasm, seeing these effigies as just souvenirs of pain and loss. And it would be easy to just appreciate it for the beautiful gowns of it all but to me, these images are beautiful because of the suffering.

Yes, the clothing is gorgeous but it didn’t fall out of a coconut tree. It’s a testament to the human condition, that even in the ugliest of times, faced with displacement, dehumanisation and destruction, people have fought to create beauty for themselves. And not just as an escape from but in defiance of the context in which they lived.

If you look outside right now, we’re not so far removed from those terrible contexts either. It’s tempting to fall victim to apathy and despair in light of the violence happening across the world right now, from my backyard in South Africa to the ongoing genocide in Palestine. And nothing ever feels like I’m doing enough.

A little after Halloween last year, just a few weeks after October 7th, I’d posted an Instagram Carousel of me and my friends celebrating Springbokoween (it was also the Rugby WC Final). And a complete stranger commented, “Here’s someone who doesn’t give a fuck about genocide.”

Now, I’ve received my fair share of mean, hurtful and asinine comments on the internet, and for the most part, they’re whatever. But I don’t think one has ever stuck with me like that before. It bothered me for days if not weeks.

This random American white girl was reprimanding me, a Black South African, about an insensitivity towards apartheid? Like, apartheid-apartheid???

It made my head spin. My immediate response was defensive, I ran through a list of my struggle credentials: she didn’t know that I’ve been pro-Palestine my whole life, that my very first friend in primary school was from Gaza and enlightened me with tales of her family’s life there, that I donated to Gift of the Givers, and that I tweeted, posted and shared information from Palestinian citizens and journalists. But, still, that comment stuck with me.

Besides the absolute absurdity of getting lectured and harassed by some rando Westerner about how good I was at performing activism online, was that she was kind of right. At the end of the day, it seems that all I can do is tap buttons on my phone and then return to regular programming. While millions of people are displaced and attacked and having the existence of their reality denied, I still go to work, forget to call my parents, eat out with friends and drink too much on the weekends. As much as we can’t stop the world and we have to do business as usual, lest we’re unable to pay rent or increase shareholder value, the least we can do is remember.

And one of the best ways I know how is through fashion.

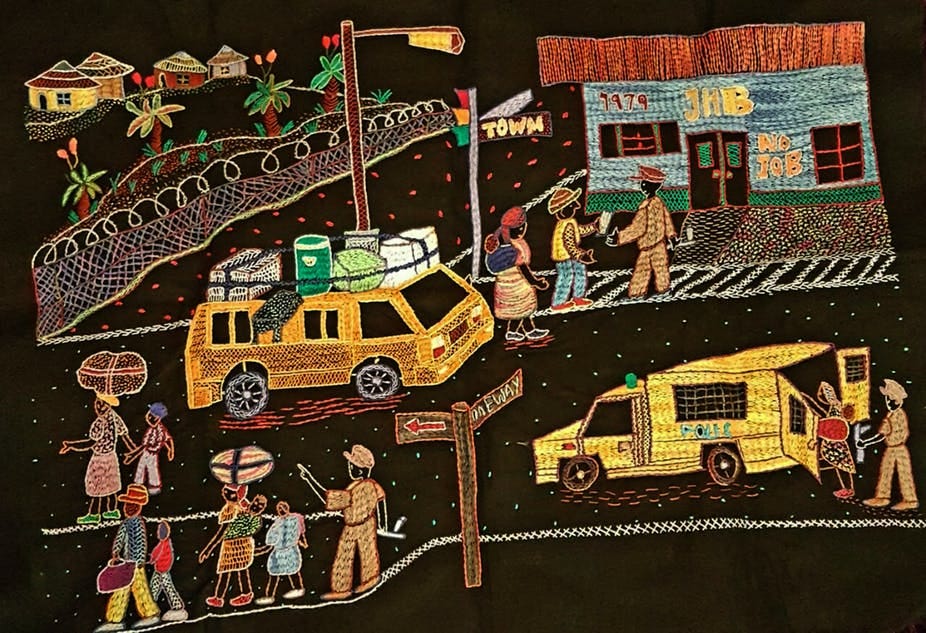

Before I moved to Cape Town last year, I went on a museum vacation in September. I was hoping to uncover more of that missing historical representation, to see proof of life for the people before me and, sadly, Cape Town has a greater abundance and access to museums than Joburg. The last stop of my trip was the District Six Museum, which was littered with textile artworks about the suburb’s history. This sparked my realisation that a lot of the history I was struggling to find in textbooks and academic articles was probably going to be discovered through cloth.

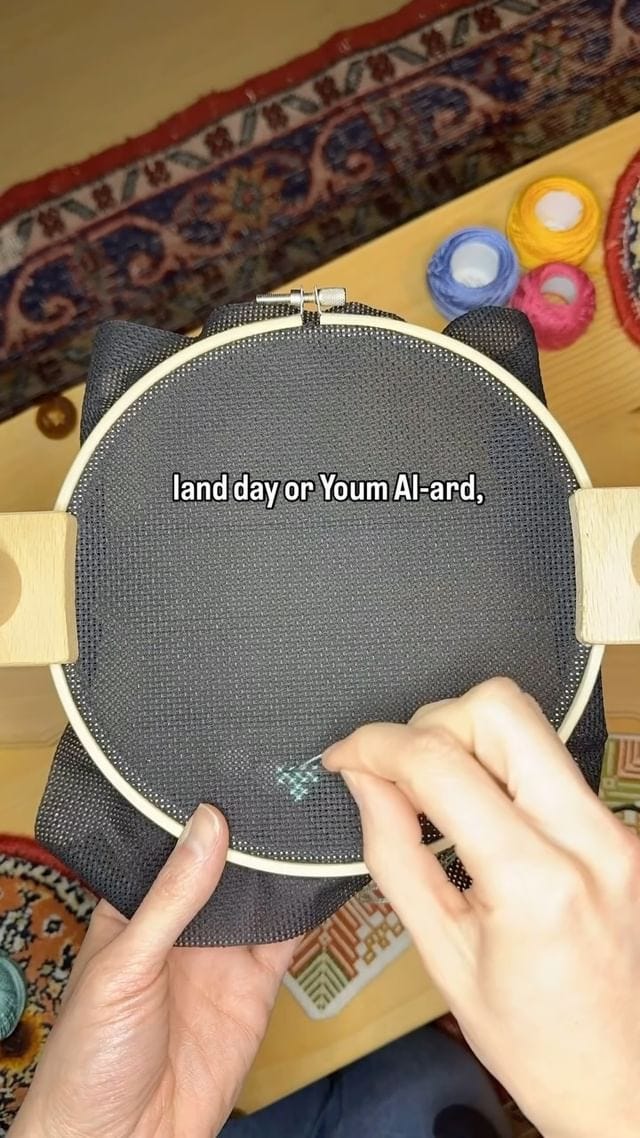

I set out to learn more about Palestinian clothing and I came across Lina Barkawi around this time. She’s a Palestinian-American tatreez practitioner. Initially, I had hoped to speak to her on my podcast about the traditional embroidery style - which she teaches online by the way, and I didn’t expect to find parallels between Palestinian and South African embroidery. Visually, they’re very different. Tatreez makes use of the cross stitch and the majority of South African embroidery makes use of chain, stem and straight stitches.

Historically, as Lina explains on my podcast, Palestinian tatreez was incredibly individualistic. The craft was passed down across generations, from mother to daughter and so on, and the motifs present in the works were reflective of the natural environment of each Palestinian woman—further proof of their indigeneity.

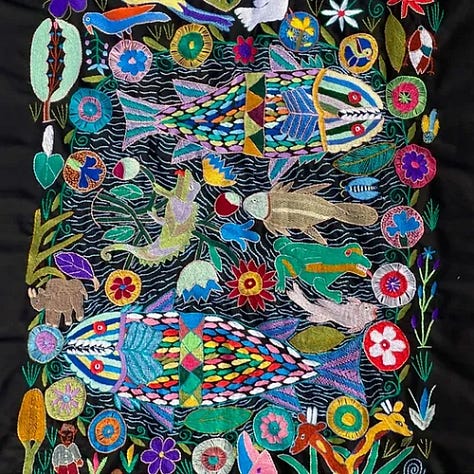

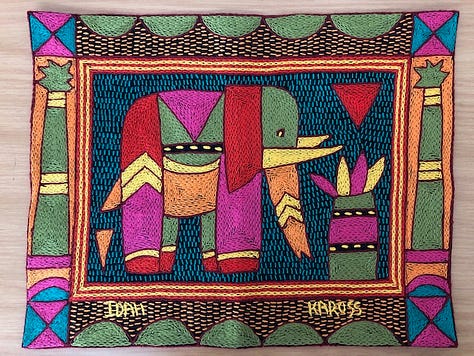

South African embroideries also draw inspiration from the natural world, often relaying folktales and mythology in brilliant colours against a black backdrop. They’re sort of like the cave painting rendered in fabric.

But what they really share in common is their use as a response to apartheid systems. As Samira states, “the dress is a rifle",” and the Palestinian thobe, a traditional dress embellished with tatreez, became a power visual signifier of resistance following the Nakba. And while embroidery was a weapon against apartheid for Palestinian women, Dr Puleng Segalo has turned it to a shield against apartheid for South African women. In 2005, she led a project with several Black women to document and heal from their experiences of apartheid. Through needlework, many of the women were able to stitch incidents that they’d never even said out loud before.

Along with Lina and Dr Segalo, I also spoke to my friend Iman Ganijee, the founder of the fashion brand, Sari for Change. Iman has a mixed heritage, from Kenya to India and South Africa, and she recently started Textiles for Justice, linking together the sartorial practices across Africa, Asia and the Middle East while advocating for solidarity and awareness.

You can listen to the whole episode below. The show notes has links to everyone featured.

Hanger Management is free today, tomorrow, and probably every day after that because social media platforms hate Africans haha. Not that you have to, but if you’d like to support me financially, you can donate any amount to my tip jar. Your contribution goes toward financing my media subscriptions, research costs, materials for sewing projects, paying my podcast editor, the odd cold one or two, and pressuring me into producing more.

Being angry all the time is exhausting and corrosive. Not being angry feels morally irresponsible. - Tim Grierson.

You know you love me

xoxo

A super poignant and lovely read.

This is the first of your newsletter posts I've read (I found you through an Instagram reel someone crossposted to tumblr) and I'm so excited to read more of your work. I love the way you write about textiles and I can already tell I'm going to learn so much from you. 🖤

Have you read Threads of Life by Clare Hunter? There are chapters in it that talk about the power of embroidery in allowing people to tell stories they had previously never been able to articulate before, a lot like you were discussing here.