Everyone gets an African fashion museum except Africa?

African fashion is everywhere except Africa.

African fashion is everywhere except Africa.

I’m going to apologise in advance if this comes off as incredibly whiney but finding out that the theme for next year’s Met costume exhibit would be “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” kind of broke me.

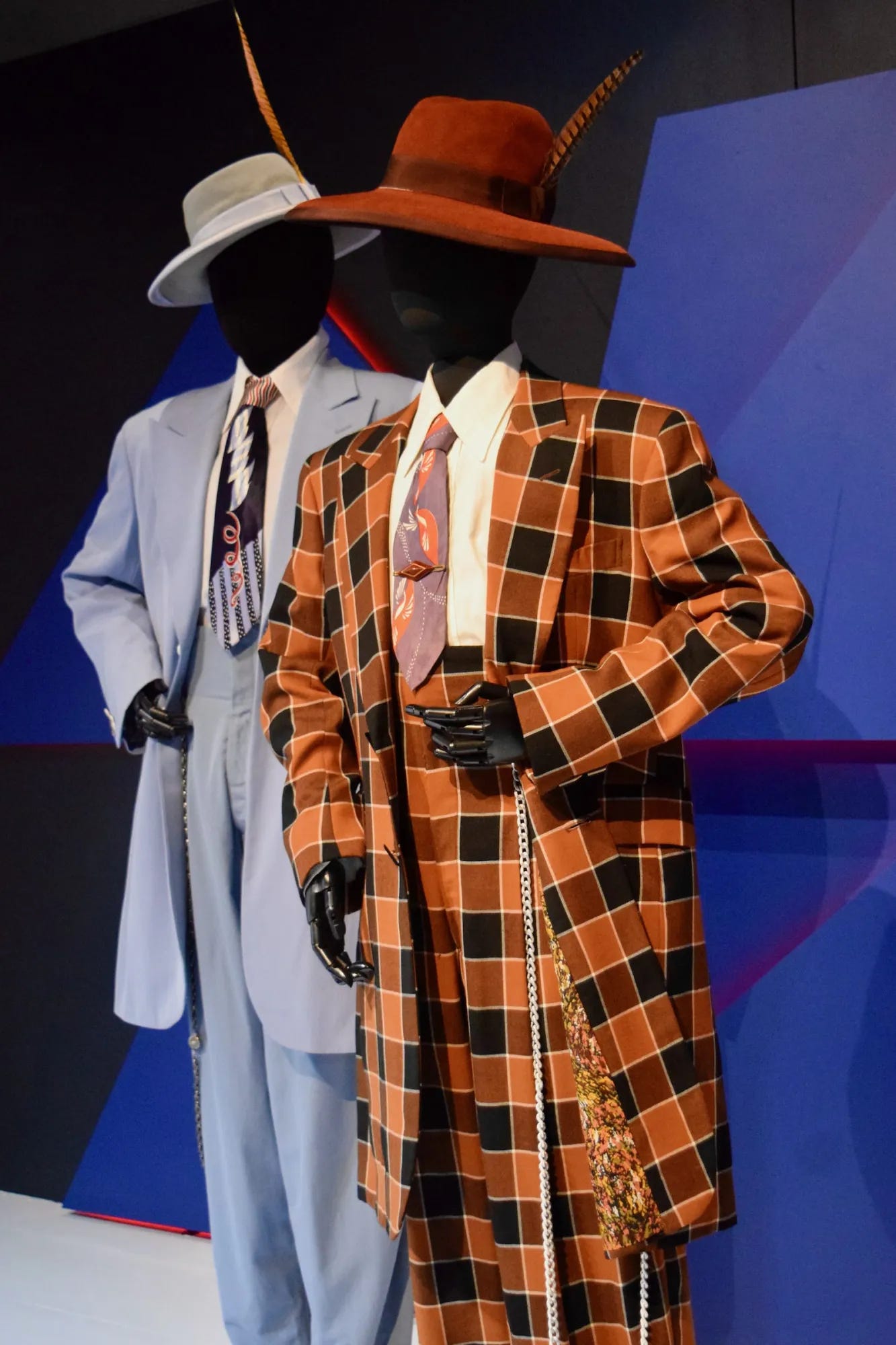

Now, don’t get me wrong, a dedicated exploration of the historical and cultural impact and contribution of Black menswear is frankly long overdue. Plus, there’s a wealth of stories and subcultures to explore. Just in Africa alone, I already think of Congo’s La Sape or South African collectives like The Sartists.

So, this should be right up my alley. Lesser known and lesser told Black/African fashion history is my Roman empire but what bugs me is that it feels like Africa isn’t included on a tangible level. (And, again, remember that I already apologised for whining.)

In the last 5 years, there’s been an increased concerted effort to platform and spotlight African fashion and design history in the hallowed halls of these large institutions.

2022 brought Africa Fashion, a first-of-its-kind celebration of the textiles, trends, images and icons who’ve shaped continental fashion from the mid-20th century to the present. I still, to this day, continuously return to the accompanying book as a master reference on specific designers, textile traditions, and ideology.

2023 saw Afrofuturism in Costume Design, a collection of over 60 of the big screen costumes created for film by one of the most prolific Black costume designers of all time, Ruth E. Carter, arrive at the Wright Museum in the US. A two-time Oscar winner for her work with Marvel’s Black Panther, Carter has been shaping the visual lexicon on Blackness on screen for decades.

Just last month, September 2024, the Museum at FIT launched Africa’s Fashion Diaspora, “explor[ing] fashion's role in shaping international Black diasporic cultures” with clothing and accessories from Black designers in Africa, Europe, the Americas and the Caribbean.

Each of these exhibitions is incredibly considered, led by the world’s leading authors and academics on African fashion such as Victoria L Rovine and Christine Checinska, and featuring influential designers past and present like Shade Thomas-Fahm, IAMISIGO, and Chris Seydou. There’s no doubt in my mind that Africa is expertly and accurately represented, and I expect The Met’s Black Dandy exhibit to follow suit (pun intended).

But how much does this matter when I watch it from a computer screen in Cape Town? We’ve yet to see any of these kinds of shows taking place on the continent. And, of course, I don’t assume this is an intentional or malicious wrongdoing by the organisers and curators. I actually imagine many of them would love to bring these displays to local galleries but, as far as I know, there are no regional institutions with costume archives to the scale of these world-renowned galleries.

It’s kind of funny because one of the reasons there’s a lack of African fashion museums was the subject of 2024’s Met showing, Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion. Textile conservation is no joke. Every second of a garment’s existence contributes to its destruction from sweat and oil produced by the human body to sun exposure and cloth-eating insects. Cloth frays, dyes bleed, and threads unravel. Textile conservation requires highly skilled restoration technicians along with technology and space to maintain that kind of upkeep.

South African museums are incredibly understaffed and underfunded but they’re also an endangered species. In 2021, we almost lost two heritage sites, Liliesleaf Farm and the Apartheid Museum from financial crises exasperated by COVID-19 (they’ve both since been rescued in the past 2 years). The Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG), home to priceless artworks from around the world, is all but falling apart, beset by rain damage, compromised maintenance and poor management from the government. On top of that, these museums can barely afford to pay well and are continuously losing labour.

In a 2020 Daily Maverick article, Karabo Mafolo explains:

There are “orphaned” collections with no curators, a lack of qualified collections staff to manage the objects, and a lack of funding to house items that are important to both the nation’s cultural and natural heritage, according to global standards.

In light of these challenges, it’s also (let’s leave it at) interesting that one of the Costume Institutes sponsors for 2025 is Africa Fashion International (a South African organisation). I’m not assuming anything but I am curious as to whether they’ve made any inroads at providing funding to local galleries and what red tape might lay there. But, also, there isn’t a clear indication of how much they’ve invested into Superfine but you have to assume it’s quite a chunk since they’re alongside Louis Vuitton and Instagram.

Hanger Management is free today, tomorrow, and probably every day after that because social media platforms hate Africans haha. Not that you have to, but if you’d like to support me financially, you can donate any amount to my tip jar or become a member of my Patreon. Your contribution goes toward financing my media subscriptions, research costs, materials for sewing projects, paying my podcast editor, the odd cold one or two, and pressuring me into producing more.

But I digress, there’s also another issue when it comes to South African museums and their textile/dress collections that I’m hoping to explore further. Many of these museums have their origins as apartheid projects and include items not always sourced with the best of intentions or methodology. In Dress As Social Relations: An Interpretation of Bushman Dress, Vibeke Marie Viestad mentions how early anthropologists would dig up graves and parade human taxidermy in pursuit of race science or to project their perceptions of indigenous populations. Large portions of beadwork, ceramics and textiles arrived to museums with little to no care detailing their meaning, significance or use (and don’t get me started on the plethora of unnamed items in the British Museum). Add to that how most museums are sights of trauma. It tickles me now to see the trashed fake Jan van Riebeck portrait at The National Art Gallery but can you imagine coming to a ‘hallowed’ institution to be constantly confronted with the idolisation of the people who’ve colonised and enslaved you?

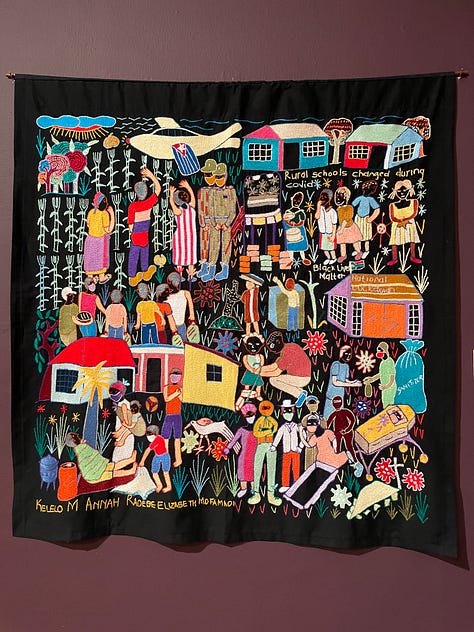

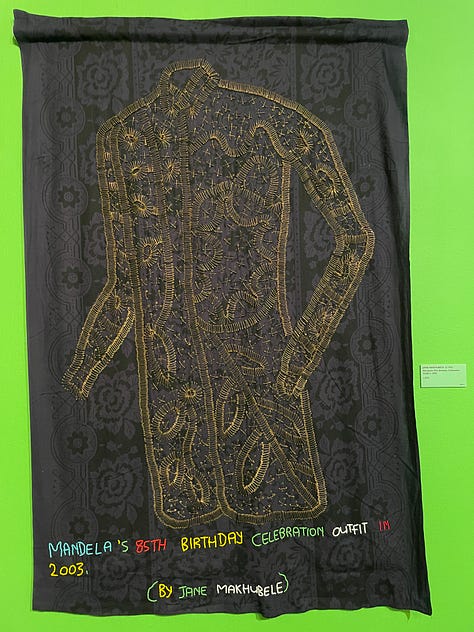

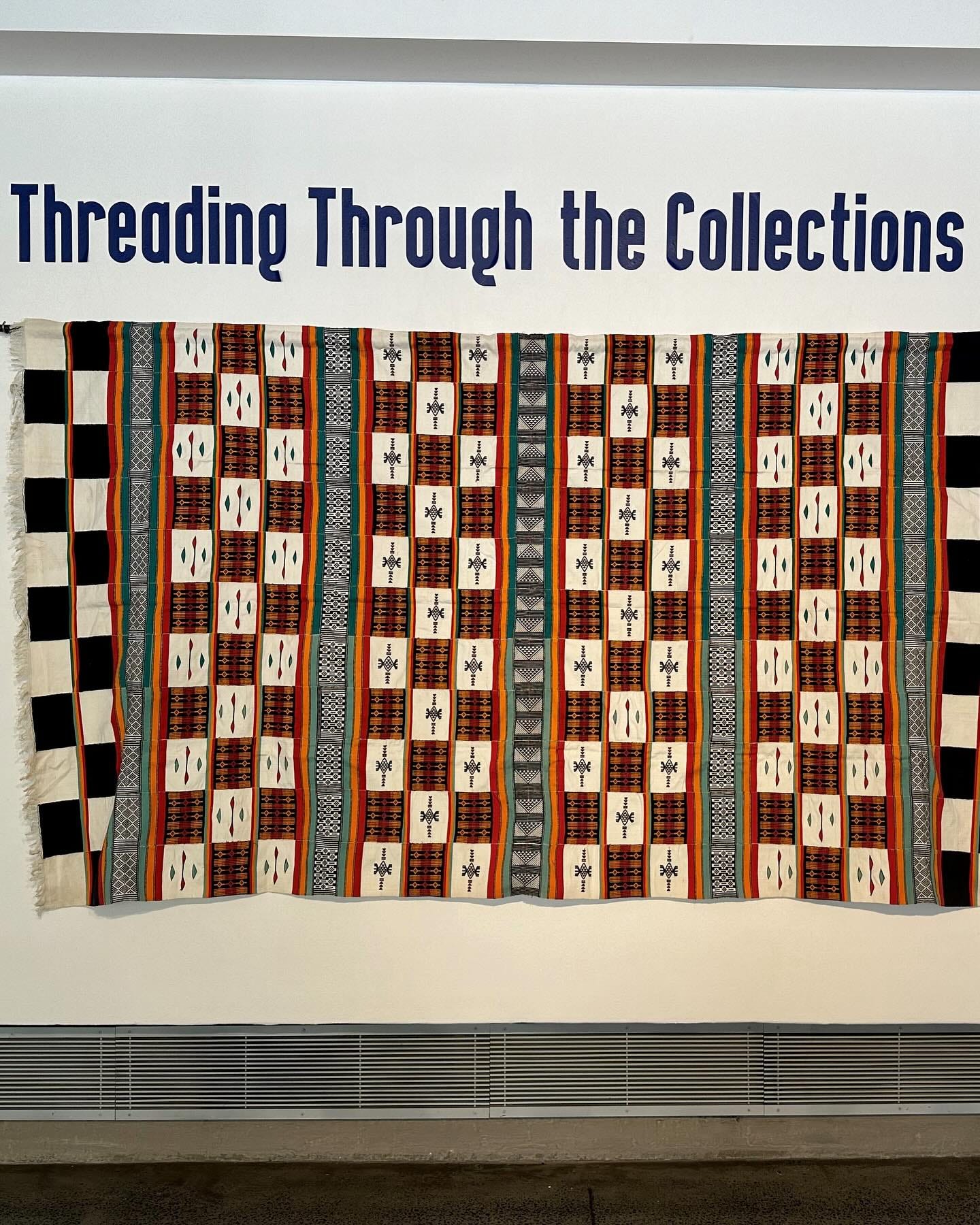

I think there’s been a lot of progress in this area in recent years. Plus some of my favourite books on South African fashion history are the result of museum projects such as Beadwork, Art and the Body from the Wits Art Museum (WAM) and Dungamanzi: Tsonga and Shangaan Art from Southern Africa from JAG. And much more recently, Kutlwano Mokgojwa curated Threading Through the Collections, displaying the many African textiles in WAM’s collection in February of this year.

I still have a lot of thinking and reading to do on this but I do hope that as the zeitgeist continues to set its eye on Africa and the diaspora we can make more inroads to include the physical continent itself.

You know you love me

xoxo Khensani

It’s a double edged sword having international organisations host Afro-related subjects in African. I personally think we (Africans) need to champion our art much more through thorough archiving & spreading accurate narratives which is of course difficult to do with half of our pre colonial creative expressions being on the other side of the ocean.

Even with the Met exhibition theme, it’s clear that it is more diasporic than having any direct influence with Africa (even though it’s obviously a trickled down effect). I’m honestly just waiting to see how it’s executed.

thank you for posting this