I am, therefore I buy: stop consuming, start creating

There are too many content recreators, we need more creators.

Welcome to the era of mass-manufactured authenticity, where our pursuit of individuality and creative expression is determined by unforgiving social media algorithms that reward conformity. It’s all about being different in the same way.

A week ago, I came across a post about the coffee tray trend—a new style of flat lay where content creators curate a selection of beverages and accessories in a cardboard tray to show off their individuality. I threw my phone at the wall.

These coffee trays were all variations of the same thing: an arrangement of cute, aesthetically pleasing items that revealed more about where you shopped than who you were. Which is how you could sum up most online trends from the past five years—from Labubu dolls to the Lizzie McGuire vlog format—where the only thing that changes is who's posting the content.

This isn’t to demonise the act of participating in a trend or wanting to be part of a group. In fact, I wish it was even more about being part of a group. I remember the Great Before, when subcultures and cliques were determined by specific tastes, experiences, and beliefs. And it was those specific tastes, experiences, and beliefs that informed what you wore and where you shopped. To identify as a punk, skater, or yuppie, you had to listen to certain music, go to particular bars, play this sport, or read that book. The way you dressed was the result of being a particular person—not the way you became that person.

The thing about basing your entire identity around products is that anyone can replicate it.

Purchased-based identity versus practice-based identity

Mandy Lee recently posted a TikTok about how we’ll never have it-girls like Alexa Chung or the Olsen twins again. The closest examples she could cite were Bella Hadid and Zendaya. And while they’re undoubtedly influential, everything about them can be—and often is—replicated with just a few clicks. The vibes, aura, and appeal of Chung, the Olsens, or even Chloë Sevigny came from the fact that the way they looked, the things they did, and the places they went were shrouded in a certain degree of mystery. They weren’t hyper-accessible, so they weren’t easily imitated. Even if you got the same bag or boots, you didn’t attend the parties or frequent the offices that led to those accessories being worn-in and scuffed.

That kind of mystique is impossible in our current age, where influence is wholly determined by a formula of novelty, accessibility, and scalability.

Take Labubu dolls, which have been in circulation since 2015. They gained traction for being weird and ugly, disrupting the feed of sameness. But once word spread and everyone could get one, we quickly entered Labubu-fatigue. The same thing happened with that AI-generated narrator trend: it was novel and different—until hundreds of tutorials popped up and it became inescapable. It went viral, the algorithm rewarded it, and everyone else joined in—until we were all sick of it.

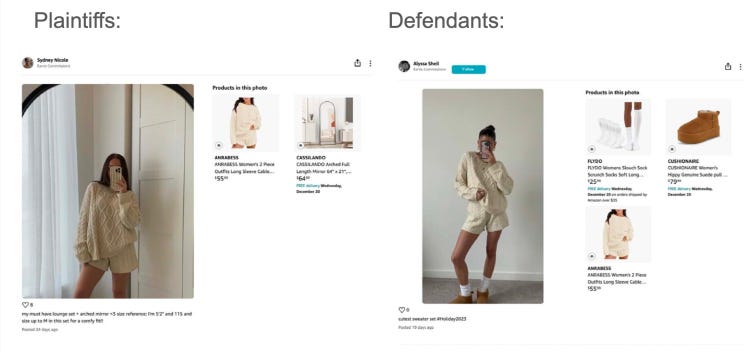

This was the core crisis of the Sad Beige Influencer lawsuit. Last year, in what felt like a Key & Peele sketch, two Amazon shopping influencers went to court over copyright infringement. Sydney Nicole Sloneker alleged that Alyssa Sheill was copying everything from her hair colour to her decorating choices—even her way of speaking and posing on camera

The case has often been mischaracterised as Sloneker trying to take ownership of the sad beige aesthetic—something now ubiquitous online—but Sloneker alleges it's about Sheill replicating her exactly, cutting into her revenue stream.

While I’m not one to discredit the amount of time and work that goes into building an online audience—and with how unprotected and fleeting the influencer industry is, I can totally understand why influencers have very little recourse outside of going after one another—it’s difficult to accept Sloneker’s claims of plagiarism when everything she herself does is a copy of a copy.

And it is the entire aim of her profession to get other people to copy her.

Every bit of her content is made to get a viewer to visit her Amazon storefront and buy her product recommendations so she can earn an affiliate commission. On top of that, there’s nothing unique about the way she does her hair, decorates her home, or speaks to her audience.

In an interview with Mia Sato about the case, Sloneker mentions some solutions to become more identifiable online, including changing where she films her unboxings, appearing on camera more, and—most sadly—“I’m going to try and make the black couch a thing. Hopefully, that becomes identifiable as my couch.”

Once more, individuality stems from a purchase.

Hanger Management is free today, tomorrow, and probably every day after that because social media platforms hate Africans haha. Not that you have to, but if you’d like to support me financially, you can donate any amount to my tip jar or become a member of my Patreon (there is a free tier, so you should join anyway). Your contribution goes toward financing my media subscriptions, research costs, materials for sewing projects, paying my podcast editor, the odd cold one or two, and pressuring me into producing more.

So, what do we do from here?

There’s nothing wrong with wanting to be part of a group or participate in a trend. I don’t think anyone is automatically devoid of character or worth because they like the same things as everyone else or want to be noticed online. Even in my idealised Great Before, subcultures still developed a kind of uniform.

What I’d like to propose is personalisation through craft. That instead of buying things to set yourself apart, you start making things. To quote my favourite YouTube video:

You’ve consumed enough. God wants you to start creating.

In Was It Something I Wore, South African jewellery designer Marlene de Beer presents the idea of craft as a form of micro-resistance. She uses her creative practice to both participate in and step outside of the social scripts dictated by her family, community, and culture.

Our online spaces can be just as rigid as the cultural environments in which we grew up. The way we dress and present ourselves is often dictated by algorithmic expectations. In a great paradox, we’re drawn to these spaces because they speak to our desire for individuality and expression—only to be flattened into cookie-cutter templates that appease an unforgiving FYP.

The speed at which trends and performances spread means we’re accumulating products faster than we can give meaning to them. It results in overconsumption—drowning in poorly made items we’ll never look at again.

And the only way out is to stop being a consumer and start being a producer.

I’m not saying we all need to start making our own clothes and jewellery from scratch, or abandon trends entirely. What I’m talking about is reclaiming identity through creative expression. Needlecrafts—sewing, beading, embroidery, crochet, knitting, etc.—offer an accessible return to true authenticity and sincerity.

De Beer argues that clothing and jewellery are to individuals what branding and PR are to corporations: a way to convey complex, coded layers of meaning. And when the wearer is also the maker, that communication becomes even more powerful—personalised, intentional, and full of nuance. Meaning and effect are constructed based on personal experience.

This is similar to what I’ve discovered about the deeply personalised craftsmanship of Zulu beadwork—and why beadwork is the subject of my upcoming workshop (shameless self-plug, I had to).

In Speaking With Beads: Zulu Arts in Southern Africa, sociologist Eleanor Preston-Whyte explains how Zulu women have historically used beadwork as a form of nonverbal communication. Functioning much like written text, they’re able to express specific messages through pattern, material, and colour.

Even though these women operate within inherited frameworks—skills passed down generationally—there are no universal meanings. Every piece is distinct. Each maker’s work is shaped by the region she comes from, any innovations or personal twists on traditional techniques, and may include secret messages decipherable only by family, friends, or lovers.

Even with the commodification of Zulu beadwork (a huge hit with the “mad ethnic” tourist crowd), its meaning hasn’t been diluted. Zulu women can produce ‘meaningless’ decorative work for sale, rooted in cultural forms, but still maintain their own private/personal, communicative practices of speaking with beads.

This balance—appeasing external forces while satisfying internal needs—is why I believe craft functions as micro-resistance.

I hope you’ll join my workshop this weekend to learn some of these skills and meet like-minded crafters. It’s beginner-friendly, open to anyone and everyone of all skill levels. We’re providing all tools and supplies. It’s happening this Saturday, 14 June, at The Creative Hub in Rosebank. You can get your ticket here.

But if you’re not in Johannesburg—or you just hate me for some reason—I hope you’ll still consider picking up any craft as your own personal form of rebellion and micro-resistance.

I’ve said before that a lot of our issues today—from a desire to return to an imaginary past to our increasing inertia and loneliness—can be diagnosed as a longing for beauty. And if there’s one thing to take from the people who came before us, it’s that beauty is in your hands.

There’s an ever-expanding universe of crafts—not just the textile-based ones I’ve mentioned—that can make life worth living.

People can resist materialistic, consumerist culture by choosing conscious creative practices. You can honour your heritage, background, or political beliefs in deeply fulfilling ways. You can take power away from gatekeepers and arbiters of culture. You can empower yourself through personal expression and the ability to make things for yourself instead of being told what to want.

You can find community.

You can build care into things.

You can create meaning.

Stop copying. Start crafting.

In other news:

I was on TV on Monday! Before a live studio audience, mind you! I spoke about apartheid trad wives on the Dan Corder Show (now available online if you’d like to check it out), based on my most recent YouTube video about the 1976 South African novel, The Virgins by Jillian Becker.

Does anyone know where I can get the ballet pink Nike Air Rifts for free somehow? It has occured to me that I have start walking more and my kitten heels are not cutting it.

You know you love me,

xoxo Khensani

The trend I have seen is people trying to fight against the idea of sameness and try to be different but still end up following trends and becoming a copy of a copy. I say this because I am trying to decorate my flat and looking online for inspiration and I’ve noticed that even the idea of “different” to a person who considers there home “different “ I swipe up and it’s someone else home looking like the same “different “ I’ve seen. Which has led to quietly log of during weekends so I can gain back introspect to what is it that I really like? , to have experiences that will inform my taste instead of an algorithm so if for me.

Craft absolutely functions as micro and “macro” resistance. There are so many examples of how we’ve used fashion, fabric, and craft to get free throughout the diaspora. I’m excited to do more research on Zulu beading!