Look at that: we’re all skhothanes now

Americans had the Satanic Panic and South Africans had Carvellas and burning piles of cash.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single South African in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a really good flex.

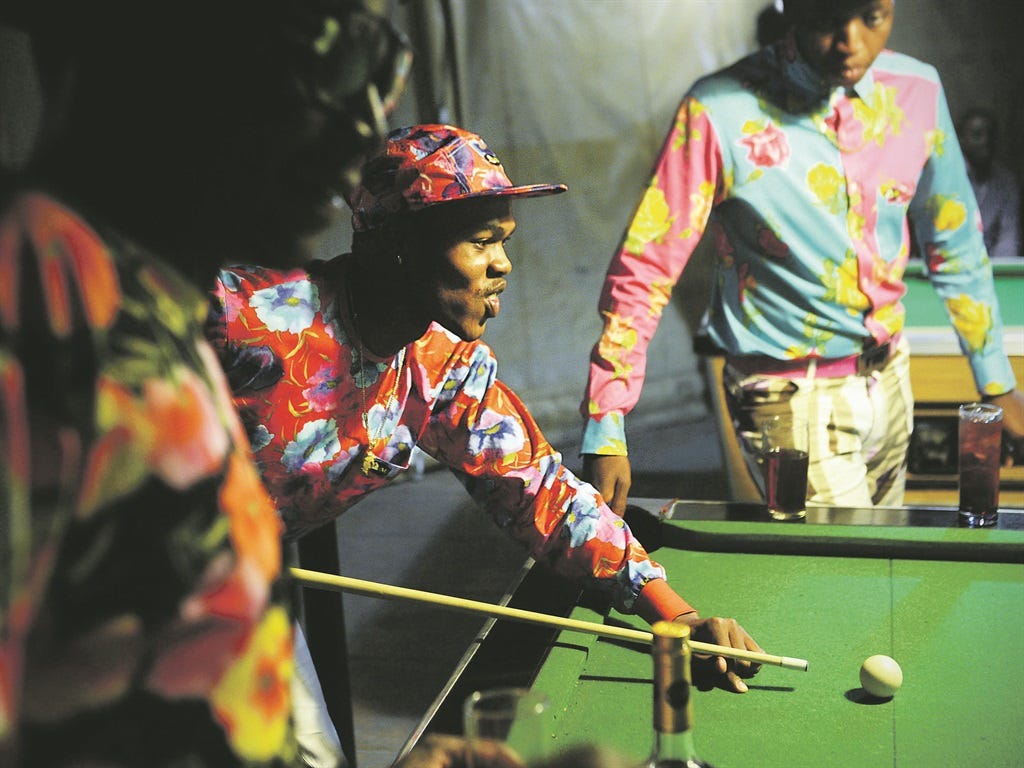

Americans had the Satanic Panic and South Africans had young men burning cash and wearing Carvellas. I’ll never forget how these stories held my nation hostage. I was maybe 14 and inundated with radio broadcasts, news programming, and newspaper articles about the decadent, cartoonish subculture emerging from the townships in the early 2010s. Izikhothane became world famous at this time for their rebellious appropriation of status signifiers against the backdrop of township life. You know, schools without latrines, pothole filled roads, crime, poverty, blah, blah, blah. The media circus always felt patronising. Like, “look at these sick, poor losers who think they can be someone through Italian leather and designer monograms, (literally) burning cash as if they’ll ever get anymore.”

It was a joke, a farce, and perhaps the first local fashion meme.

When I got to fashion school and started theorising, critiquing, and analysing, I learnt that izikhothane were involved in an act of post-apartheid anti-fashion. They were playing a game of refusal and reversal. They refused to accept the positions and status given to them, and they reversed how we interpreted these material symbols of wealth, prosperity and dignity. The real joke was on the people who placed their worth and value in these things–things that anyone, even some kasi guy, could attain.

Fashion has long played an important role in class distinction in society. Georg Simmel argues that fashion only persists because of class. It is because of the upper class’s desire to differentiate themselves from commoners that newness must constantly be engineered. Simultaneously, it is the lower class’s desire to achieve upward mobility that trends and styles are disseminated throughout society. Bank accounts, heritage, and pedigree are invisible to the naked eye and as people move through society we need instantaneous methods to communicate our position and status. Your value, respectability, career, rank and social position are visually communicated through products. The problem with products, however, is that they’re rather easily appropriated. Whether through theft, dupes, knockoffs, it’s plausible for anyone, of any class, to dress like an Olsen or Oppenheimer.

Sumptuary laws were introduced to solve this problem. Legally enforceable regulations on who gets to wear what. In the 18th century Dutch Cape Colony, only members of the VOC and their wives were allowed the finest silks, parasols, pearls and gold shoe buckles (source). In the 1760s, free black women were prohibited from wearing colourful silks, precious stones and ornate lace caps as this placed “[them] not only on a par with other respectable burghers’ wives, but often pushed themselves above them.” (source) Lower class people being fashionable is a threat to stratification. It’s always made people uneasy.

It’s tempting to look at most post-apartheid fashion culture and identity as an attack on notions of class and race in our Rainbow Nation. Black Diamonds, the newly emerged class of upwardly mobile Black South Africans, drive Porsches, wear Gucci and eat sushi because it signals their arrival to acceptance and equality. Or maybe it’s another joke. Maybe it’s a commentary of how meaningless these symbols of which you’ve denied us so long are. Not only can we all go to Diamond Walk, but I could very easily stroll down to Small Street and get a Fendi tracksuit or purchase a convincing Louis Vuitton Alma dupe from GALXBOY. “Your symbols are silly so I’ll bastardise them.”

Izikhothane disappeared like a hot flash. You’d be pretty hard pressed to find anyone talking about them post-2017, at least not to the extent it occupied the zeitgeist in the early 2010s. The pearl clutching has disappeared, the jokes are no longer made, the academic articles have stopped. There’s a notion that it’s over, that the whirlwind of media attention and moral panic pretty much killed the subculture as it began.

I think of skhothane culture like a really good meme in that, once everyone’s joked about it or engaged ironically enough, it just becomes a part of the lexicon. The subculture didn’t die, it just became a part of the culture. When you look at mainstream fashion identity in South Africa, it’s just repackaged skhothane in different forms. Instagram influencers with Hermes handbags who need crowdfunding to pay their school fees. A fashion designer who made enough money off of bootleg Gucci shoes to kit his girlfriend out in genuine Louis Vuitton. Coming home sticky from the club because some big baller decided to make it rain Veuve.

But, I don’t know, I think the joke’s gotten pretty stale. It’s increasingly difficult to see celebrities and influencers and the media propagate this luxurious lifestyle when, more often than not, it’s the result of ill gotten gains. It was one thing for izikhothane to be washing their hands in whiskey while surrounded by potholes and streetlights that have never worked because that was legitimately beyond their control. However, the Diamond Walk, home to international luxury brands, is frequented by the kind of people embroiled in corruption and looting scandals. It often seems the only way to make it as a beauty guru is to have a boyfriend whose father might be the reason why our trains don’t come on time. There are politicians in the section at the club and they’re spending school fees on baddies.

It’s like a Xerox of a Xerox, to quote Bojack Horseman. It’s lost all its meaning and now we’re left with these grainy, pixelated messages that mean nothing to no one.

I wrote this last year for my dearly departed friend, Uli’s book of fashion essays which probably won’t get published. They ran a great Substack called That’s Gossip and could always be relied upon for the best breakdowns and analysis of fashion collections and industry happenings. With the Met Gala this evening, I’ve been thinking of the hole left by their absence and wondering who else could give a scathing appraisal of the looks tonight. Rest in Prada, my friend.

References

Andrew Thompson, 2017, Remembering the Legacy of This Clothes-Burning Subculture in South Africa

Busisiwe Sanelisiwe Memela, 2017, ‘Swag’: an ethnographic study of izikhotane fashion identity

James Grant Richards, 2015, Izikhothane: Masculinity and Class in Katlehong, a South African Township

Liza-Mari Coetzee, 2015, Fashion and the World of the Women of the VOC Official Elite

Robert Shell, 1992, Tender Ties: Women and the Slave Household, 1652-1834